The Tour du Mont Blanc is not just a great classic of the Alps: it is a lively crossing, both sporty and accessible, linking inhabited valleys, panoramic passes, and refuges where one shares the table with hikers from everywhere. Over approximately 160 to 170 km and nearly 10,000 m of cumulative positive elevation gain, the route draws a loop around the Mont Blanc massif, passing through France, Italy, and Switzerland. Most hikers complete it in 7 to 12 days depending on pace, training level, and chosen logistics. In 2026, the success of the TMB remains unwavering: refuges are often full, trails are very busy in mid-summer, and the weather requires more than ever the ability to adapt.

To make this guide concrete, we will follow the thread of a realistic preparation, that of Claire and Mehdi, two friends who want to go without a guide but with method. She hikes regularly, he is discovering itineraries: they seek a reliable plan, understandable stages, and solutions if everything does not go as planned. Between choosing the direction of travel, booking nights, managing thunderstorms, water, safety, and possible small hassles (such as bed bugs), the goal is simple: to transform a “big project” into a well-framed adventure, without losing the magic of the terrain.

Tour du Mont Blanc: Understanding the Route, Duration, and Best Season

The GR Tour du Mont Blanc is a marked alpine loop that crosses three countries. It is often associated with a “classic” breakdown of about 10 days, but the reality is more flexible: some hikers aim for 7 to 8 days (sporty pace), others prefer 11 to 12 days to enjoy villages, breaks, and wilder variants. In all cases, the experience is marked by diversity: alpine pastures, forests, moraines, scree slopes, inhabited valleys, and mountain passes. This constant contrast explains why the TMB remains motivating day after day.

Claire and Mehdi hesitate between 9 and 10 days. Their main criterion is not performance: it is the ability to chain several days of walking, carry a backpack, and remain clear-headed on descents. It is a good reading grid: on the TMB, the difficulty is less “technical” than “cumulative.” One can feel strong in the morning, then realize at 4 p.m. that repeated elevation gain eventually wears down the thighs, especially if pace is badly managed.

Mid-June to Mid-September: Ideal Window, but Not Uniform

The most favorable period is generally from mid-June to mid-September, when refuges are open and passes are more passable. However, conditions change radically depending on the weeks. Early June can still have snowfields on the high passages, with very real consequences: long slips, reduced visibility, and extra mental fatigue. In these scenarios, equipment and skills must keep up: stiffer shoes, sometimes crampons and an ice axe for exposed sections, and stricter risk management. Trail running shoes, enjoyable on dry terrain, become unsuitable on hard snow during pass crossings.

Conversely, July-August generally offers milder temperatures and a well-marked path, although some snowfields persist. The downside is the crowd: many hikers start from the Les Houches and go counterclockwise. To find calm without changing the date, a simple strategy is to walk in the clockwise direction: you will then cross the main flow around the pass at lunchtime, and much of the day passes more quietly.

In September, the atmosphere changes. Mornings are cool, first snow can reappear, and some water points become less regular. Refuge teams sometimes come out of intense months: service can be more minimal without detracting from the charm of the places. Counting on an “Indian summer” often works, but you have to accept the idea of last-minute adaptation.

Access, Departure, and Options to Modulate the Adventure

The most common starting point remains Les Houches, easily accessible from the Chamonix valley. For the arrival, the loop allows returning to the same place, simplifying car or train logistics. If you travel via Geneva, allowing some margin is useful: a missed connection can disrupt a first night booked well in advance. To prepare a transit and possibly add a visit before departure, a detour to Geneva’s must-see places can also serve as a buffer before the mountains.

Finally, the TMB lends itself to adjustments: valley buses, occasional ski lifts, taxis to skip an uninteresting section or avoid a thunderstorm. This modularity does not detract from the experience: it often makes it more sustainable, as it avoids turning an unforeseen event into a failure. The real luxury on the TMB is knowing how to change plans without losing track.

Physical and Mental Preparation for the Tour du Mont Blanc: Endurance, Elevation Gain, and Effort Management

Preparing for the TMB means preparing a sequence of days: walking long, climbing, descending, repeating. Good physical condition does not mean running fast; it means maintaining a steady pace, limiting pain, and recovering enough to set off again the next day. Claire already trains on weekends, but Mehdi’s activity is mainly urban. Their plan is therefore simple: build an endurance base, then accustom the body to elevation gain and carrying weight.

Effective preparation ideally spans 8 to 12 weeks: it’s enough to progress without injury, and short enough to stay motivated. A common mistake is to “do a lot” all at once. On the TMB, overuse injuries (knee, Achilles tendon, iliotibial band) cost more than any equipment: they turn a beautiful trek into abandonment.

Realistic Training Plan: Walking, Climbing, Carrying

The foundation is regular outings on varied terrain. Two weekly sessions often suffice: one short but dynamic, one longer and peaceful. The goal is not to be breathless; it’s to be able to talk while walking. Then, add elevation gain: stairs, hills, local hikes. If you are in Haute-Savoie before departure, drawing ideas from walks and hikes in Haute-Savoie helps vary profiles and work on consistency.

From the fourth or fifth week, Claire suggests a rule to Mehdi: walk with the backpack, even if it is not yet loaded as on the trek. The back, shoulders, and hips progressively adapt. The day you leave with 8 to 10 kg, you’ll be glad to have “tested” the shoulder straps and hip belt beforehand.

Effort Management Over Several Days: Pace as a Safety Tool

On the TMB, starting too fast in the morning is a classic mistake. The heart rate follows, ego too, then the day ends with cramps on a steep descent. A robust strategy is to mentally break down each stage: a main climb, a plateau, a descent, then the “end of the day.” At each segment, ask yourself: “Am I walking sustainably?” This simple check prevents drifting.

Breaks should be short and frequent. A 2-minute break to drink and eat every 45 minutes is better than a 25-minute stop where one cools down. In the passes, the moderate altitude (often between 2000 and 2500 m) does not necessarily cause acute mountain sickness, but some people still experience headaches and nausea. In that case, hydration, slow pace, and stopping are priorities.

Mental Preparation: Motivation, Weather Stress, and “Plan B” Scenarios

The psychological dimension is underestimated. The TMB can string together three splendid days, then offer rain, fog, and wind. Mehdi fears “not seeing Mont Blanc.” Claire reframes: “We are here to tour a living massif, not for a single photo.” This change of objective reduces frustration.

Managing stress also involves alternative plans: knowing where the valleys are, which buses exist, which refuges are nearby. Having this information does not cause anxiety; on the contrary: it gives a sense of control. When the mind is calm, the legs follow. The logical next step is therefore to equip oneself to remain comfortable, even when the mountain complicates the game.

Essential Equipment for the TMB: Bag, Clothing, Safety, and Comfort for 7 to 12 Days

Equipment on the Tour du Mont Blanc is not an accumulation of objects: it is a coherent system aiming at three results. First, walking without pain. Then, staying dry and warm despite rapid changes. Finally, managing an unforeseen event without immediately depending on others. Valentin Gevaux, guide on the route, often sums up common sense this way: “Equipment doesn’t prevent mistakes, but it reduces their cost.” Claire and Mehdi understood this by testing their gear on a day hike before booking all their nights.

The Basics: Shoes, Backpack, Technical Layers

Shoes are the number one element. A mid-height upper can reassure on descents and protect from shocks, whereas a low upper suits hikers very accustomed to terrain. The important parts are the sole, grip, and absence of blisters. New shoes the day before departure remain the most costly bad idea of the season.

The backpack depends on the type of accommodation. In refuges, a volume around 35 to 45 L often suffices. For bivouac, one easily goes up to 50-60 L, with a weight increase paid in elevation gain. Adjustment is crucial: the belt must carry most of the load, not the shoulders. A well-fitted pack is almost “forgotten.”

Concerning clothing, the principle of three layers remains the most reliable: a breathable layer, a warm layer, a wind/rain protection. Even in summer, a collar can be cold, especially if you’re wet or immobile. Adding a pair of light gloves and a neck gaiter is often more useful than an “extra” bulky garment.

Safety Equipment: What Is Rarely Used… But Sometimes Saves

A headlamp allows managing an early start to avoid thunderstorms or a late arrival without panic. A simple but thoughtful first aid kit (blister plasters, tape, disinfectant, anti-inflammatory if compatible, survival blanket) is a standard. Add a map or guidebook, even if marking is good: fog turns an “obvious” trail into a labyrinth.

In 2026, many hikers also rely on communication means: iPhones compatible with satellite emergency calls (from some recent models), dedicated beacons, even satellite phones for autonomous groups. This is not mandatory but can reassure. Keep in mind that there are no-coverage zones in some valleys, on the Savoie or Swiss side.

Recommended Equipment List (Refuges, No Bivouac)

- Hiking boots already broken in + technical socks (2 to 3 pairs)

- Backpack 35–45 L + rain cover

- Waterproof jacket (membrane) + light fleece or compact down jacket

- Walking pants + shorts (optional) + thin warm layer

- Hat or headband + thin gloves + neck gaiter

- Trekking poles (very useful on descents and unstable terrain)

- Water bottle or reservoir (1.5–2 L) + filtration system/tablets

- Headlamp + external battery

- First aid kit + survival blanket

- Sleeping sheet for refuge + earplugs

To limit forgetfulness, Claire packs her bag in “blocks” (clothes, hygiene, safety, electronics) in waterproof pouches. This method becomes valuable in refuges: you pack quickly, avoid scattering your stuff, and also reduce risks related to bed bugs by better isolating your gear.

Table: Simple Benchmarks to Choose Your Itinerary Format

| Option | Average Backpack Weight | Freedom | Constraints | Typical Profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Refuges / Hostels (half board) | 7–10 kg | Medium | Early reservations, higher budget | Beginner to experienced seeking comfort |

| Mix of refuges + campings | 9–13 kg | Good | Variable logistics depending on country, weather | Autonomous, flexible walker |

| Mostly bivouac (suitable) | 12–18 kg | High (in theory) | Strict regulations, increased fatigue | Experienced, organized, minimalist |

With this material base, the next question naturally becomes: where to sleep, how to book, and how to eat without carrying unnecessary load. This is often where the TMB is won… or complicated.

Accommodation and Provisioning on the Tour du Mont Blanc: Refuges, Campings, Bookings, and Water Management

On the TMB, accommodation influences almost everything: backpack weight, daily pace, budget, and even serenity in the face of unforeseen events. Claire and Mehdi choose predominantly refuges and hostels, with one or two nights in the valley to rest. It is the most common choice, notably because bivouac is very regulated or even forbidden in some sectors.

Many refuges are staffed from mid-June to mid-September. At early June or starting mid-September, some establishments close, and options decrease, especially on the Italian side. Booking is therefore a central issue. Some structures even open quotas to tour operators very early, which can give the impression that “everything is full” long in advance.

Booking Smartly: Flexibility, Valleys, Shuttles

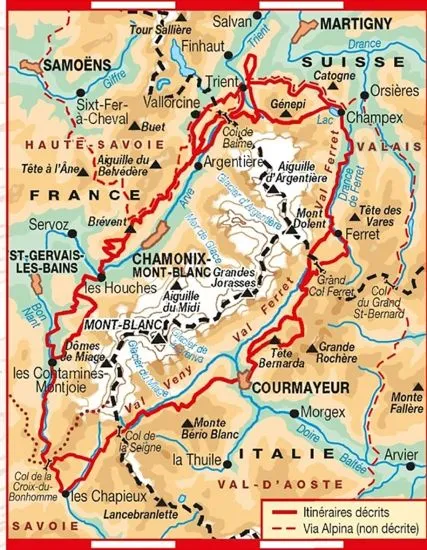

When a key stage is saturated, the solution is not necessarily to give up: it is to shift a night in the valley. For example, Trient in Switzerland fills up quickly. An alternative is to sleep farther and rejoin the route the next day thanks to a shuttle or taxi, like towards Martigny depending on availability. On the Italian side, buses (often very practical) regularly connect Val Ferret, Val Veny, and Courmayeur, allowing bypassing a lack of space without breaking the whole loop.

In the Chamonix valley, buses also facilitate adjustments. This “soft mobility” is a safety net: it helps manage announced storms, beginning tendinitis, or delays due to weather. The key is to keep a simple fallback plan: accommodation in the valley and a way to get down there.

Bivouac: Rules by Country and Best Practices

Bivouac is not just “pitching a tent wherever you want.” In Switzerland, it is forbidden in the valleys concerned by the route. In Italy, it is often very constrained, and tolerance is limited; campgrounds in some areas (Trient, Champex, Val Ferret, Val Veny) then become realistic solutions. In France, bivouac is frequently tolerated from evening to morning, with precise rules (often around 7 p.m.–9 a.m.) and restrictions in some natural reserves, where permit systems have been implemented in recent years. Before considering a night under a tent, consult the Good Practices Guide for Hiking to frame behavior and avoid mistakes that upset locals and protected area managers.

Managing Food: Energy, Simplicity, Budget

Most hikers alternate half board and purchases in villages. In refuges, one often sees a price order: around €50 per person for half board, €10 for a prepared picnic, and €10 to €15 for a midday meal. These references help build a coherent budget. For Claire and Mehdi, the rule is simple: dinner and breakfast in refuges, and a mixed lunch (picnic + supplements bought in the valley) to limit spending without deprivation.

The food contents in the backpack should remain light and caloric: nuts, dried fruits, cheese, bread, bars, chocolate. A “treat” can also become a mental tool: a square of chocolate at the pass is sometimes what keeps you going.

Water on the TMB: Abundant, but Not Always Guaranteed

Water is generally present on the route via fountains, streams, and refuges. In drier periods, some places ration, and availability decreases at late summer. A practical rule works well: fill up whenever water is accessible, without waiting to be out. For those drinking in streams, take water high up the course, away from herds and very frequented areas. To minimize risks, filtration or tablets remain simple solutions.

At this stage, Claire and Mehdi have their night plan and their water/food routine. The most awaited part remains: breaking down stages and variants, to transform logistics into a real crossing.

Seeing images of typical stages helps visualize climb profiles and trail width, but nothing replaces a careful reading of distances and elevation gain before committing.

Itineraries and Stages of the Tour du Mont Blanc: Breakdown into 10 Days, Variants, and Weather Plan B

The TMB can be divided in many ways, but the 10-day format remains a balanced reference: progressive enough to enjoy, structured enough to book. The goal here is not to impose “the” good plan but to give a solid framework that you will adjust according to available nights, your shape, and conditions. Claire and Mehdi choose a 10-day base with two levers: shorten a stage if the weather deteriorates, or conversely lengthen it if a variant is passable.

Recommended Breakdown in 10 Days: Distances, Time, and Interest

The times indicated below are estimates of “easy” walking excluding long breaks. In mountains, terrain and weather conditions can greatly stretch the actual duration. The principle is to start early, especially in summer, to limit exposure to afternoon thunderstorms.

- Les Houches → Refuge de Nant Borrant: warm-up, first alpine pastures, 5–7h depending on variants.

- Nant Borrant → Les Chapieux / Ville des Glaciers: open landscapes, important pace management, 5–7h.

- Ville des Glaciers → Refuge Elisabetta: Italian side passage, high mountain atmosphere, 6–8h.

- Refuge Elisabetta → Courmayeur / Refuge Bertone (depending on option): views on the Italian side, marked descent, 5–7h.

- Courmayeur / Bertone → Val Ferret / La Fouly: valley route, 6–8h depending on arrival.

- La Fouly → Champex-Lac: more rolling stage, useful for recovery, 4–6h.

- Champex-Lac → Trient: relief getting steeper, forests and balconies, 5–7h.

- Trient → Tré-le-Champ: gradual return on France side, varied terrain, 6–8h.

- Tré-le-Champ → La Flégère: views of Aiguilles and glaciers, technical sections, 5–7h.

- La Flégère → Les Houches: end of loop, alternating balconies and descents, 5–7h.

Variants: Beauty, Difficulty, and Objective Vigilance

Variants are often the most beautiful days… and sometimes the most demanding. The Fenêtre d’Arpette attracts for its mineral ambiance and “mountain” character. It requires stable weather, good reading of the terrain, and particular attention to rockfalls, which have become more frequent in the Alps with freeze/thaw cycles at altitude. Another zone requiring caution is near the Col des Tufs (between Col du Bonhomme and Lacs Jovets), where some unstable sectors encourage crossing quickly while staying alert to sounds and movements.

In doubt, the best decision is often the simplest: stay on the main route or drop down to the valley. This choice is not a surrender; it’s a way to safely complete the loop.

Thunderstorms: Daily Organization and Useful Behaviors

On the TMB, summer thunderstorms often arrive in the afternoon. The 48-hour forecast gives a trend, but it becomes more precise in the morning. A concrete strategy is to discuss with the host: advance breakfast, start earlier, or organize a transfer if a ridge is expected under lightning.

Radar apps like MétéoSwiss are particularly useful to visualize the arrival of a storm cell in a few hours. This doesn’t replace judgment on the ground but helps make clear decisions. If caught by a storm, a few simple rules make the difference: avoid high points, don’t cling to a lone tree, stay away from runoffs under overhangs, move metal objects aside, and isolate from the ground by sitting on the pack. The storm is generally considered over about 30 minutes after the last thunderclap.

With a clear route, variants chosen for good reasons, and a method for weather, the last layer of preparation concerns health, safety, and those small “invisible” risks that sometimes spoil the return.

Health, Safety, and Practical Advice on the TMB: Rescue, Water, Rockfalls, Hunting, and Bed Bugs

On a trek like the Tour du Mont Blanc, safety is not an isolated chapter: it’s a way of walking. It starts with lucidity (knowing when to give up a variant), continues with anticipation (starting early), and extends into refuges (hygiene, rest, discreet vigilance). For Claire and Mehdi, the goal is not to become experts but to adopt reflexes that avoid 80% of problems.

Rescue and No Coverage Areas: What to Do if Things Go Wrong?

The European emergency number 112 works in all three crossed countries. An important point: if your operator has no coverage, calls can sometimes switch to another available network. Despite this, some sections remain white zones. Hence the interest in spotting, on the map, the position of refuges and valley accesses: knowing where to descend is often more useful than “searching for a bar” of network.

Satellite means (beacon, satellite phone, integrated services on some recent smartphones) add safety, especially for small groups. They don’t replace fundamentals: protecting the victim from cold, managing the wait, and transmitting clear information (precise location, condition, weather).

Altitude Sickness and Fatigue: Weak Signals to Take Seriously

The TMB stays at moderate altitudes, but some hikers are sensitive. Headaches, nausea, dizziness, abnormal fatigue: these are signals to listen to. The primary response is simple: slow down, drink, eat, then decide. If symptoms persist, descending is the most effective solution. Pride doesn’t help breathing.

Rockfalls: Increased Risk in the Alps

Warming and freeze/thaw cycles weaken rocks at altitude. On the ground, this translates into concrete advice: in scree and debris cones, cross quickly without lingering, keep eyes and ears open, and avoid stopping below unstable slopes. This is not alarmist: it’s a progression hygiene. To understand how some mountain tragedies occur, reading this article about accidents and risks in the mountains puts simple decisions into perspective.

Hunting in September: Visibility and Caution Off Trail

In autumn, hunting reappears. Rules differ by country and sometimes by valley. If you plan variants off the route, wear brightly colored clothing and signal your presence in dense vegetation areas. A discreet but regular noise is better than surprise effect.

Bed Bugs: Reducing the Risk Without Obsession

The subject is sensitive but real: bed bugs can appear in refuges and hotels. The main danger is not the bite; it’s bringing the insect home. Some habits significantly reduce the risk: quickly inspecting the mattress (small dark or reddish spots), keeping belongings gathered in waterproof bags, avoiding spreading clothes and bags on carpets or beds, and alerting the host if suspected so a protocol is triggered.

Some use a light spray (including tea-tree diluted solutions) on closures and contact zones without believing in a miracle cure. In case of doubt after a night, isolate clothes in a closed bag and treat upon return: freeze at -18°C for 72 hours for fragile textiles or high heat for those that tolerate it. This rigor, applied calmly, avoids many complications.

Round Trip Logistics and Recovery “Buffer”

Finally, success on the TMB also depends on what you do around it: sleeping well the night before, arriving with margin, and planning a “buffer” day afterward. Some enjoy this return to slow down near water or on easy routes; others extend with an easy hike. The essential is to come back without rush because a trek rarely ends when you put down the pack: it ends when the body has recovered.

With these health and safety benchmarks, you have a solid base to go autonomous, adjust your plans, and keep pleasure central, even when conditions change.

Video feedback is useful to visualize behaviors to adopt in case of storm or fog, and to better understand how hikers manage daily timing.

How many days should you plan for the Tour du Mont Blanc when starting trekking?

A 10 to 12-day format is often the most comfortable for a first itinerant trek: shorter stages, better recovery, and more margin in case of unstable weather. If you are already comfortable with 6 to 8 hours of mountain walking, 9 to 10 days can suit. The decisive criterion remains the ability to chain several descents without pain.

Is it really necessary to book refuges long in advance?

Yes, especially in July-August and in Swiss and Italian areas where bivouac is very limited. Early booking secures your itinerary. If full, favor a flexible strategy: valley nights, shuttles/buses, or slight shifting of stages rather than abandoning the project.

What is the best strategy against thunderstorms on the TMB?

Start early and keep a Plan B. Storms often come in the afternoon: an early start helps cross passes before the most exposed period. Check forecasts the same morning and use a weather radar to track short-term changes. If threatened, renounce a ridge variant and descend to a valley or refuge.

Can the TMB be done only by bivouac?

It is possible but restrictive. Bivouac is forbidden in Switzerland in the concerned valleys and highly regulated in Italy, often requiring camping or accommodation. In France, it is frequently tolerated from evening to morning depending on sectors, with specific rules in reserves. Many hikers choose a mix of refuges plus some camping nights to keep a reasonable backpack.

How much water should you carry for a typical day?

Under normal conditions, 1.5 to 2 liters often suffice if you refill regularly at fountains/refuges and temperatures remain moderate. In hot periods or on a drier stage, aim for 2 to 2.5 liters. A filter or tablets provide a safety margin if you must drink from natural sources.