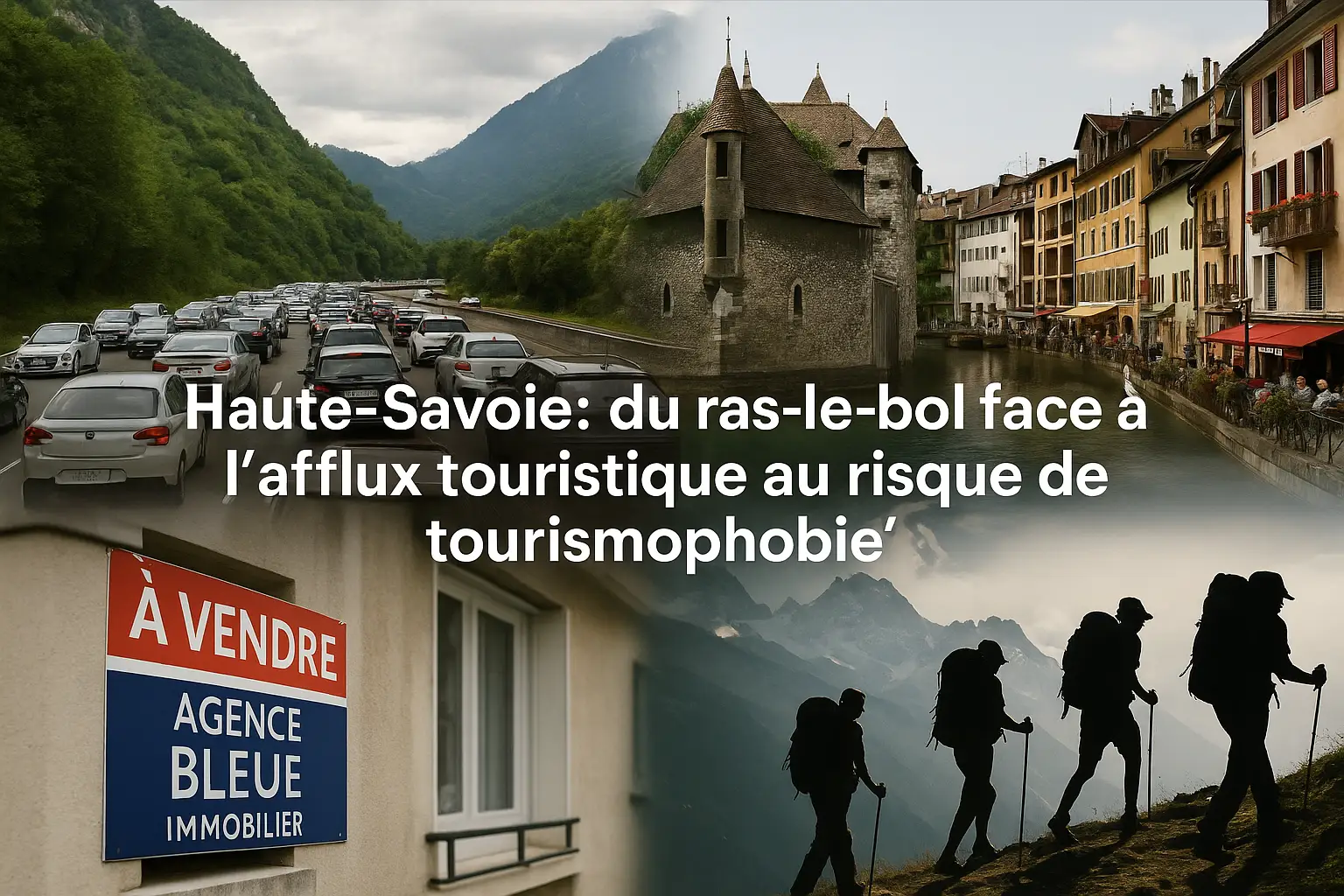

Being a land of mountains, lakes, and picturesque villages attracts millions of visitors each year. But in Haute-Savoie, this appeal is beginning to raise tensions. Between summer congestion, soaring property prices, and a sense of dispossession, the line between criticism of mass tourism and outright rejection of visitors is becoming increasingly blurred.

A sought-after… and saturated territory

With its iconic sites, Annecy, Chamonix, Yvoire, the shores of Lake Geneva, and the Aravis massif, Haute-Savoie is among the most touristy departments in France. In winter, the resorts are fully booked; in summer, the banks of the Lake Annecy or Geneva see their roads blocked, parking lots full, and rents soaring.

The residents, especially in the busiest areas, express growing discomfort: “we can no longer get around,” “everything has become unaffordable,” “local shops are disappearing in favor of holiday rentals”… so many complaints that often target the same culprit: the tourist.

When criticism becomes rejection

Behind these legitimate complaints sometimes hides a more virulent discourse. Some denounce “foreigners invading the lake,” others regret “the disappearance of the local soul.” A rhetoric that echoes what geographers now call tourismophobia: distrust, even rejection, towards those who come to discover a place.

According to researcher Jean-Christophe Gay, this phenomenon is more about a fear of the other, close to what he calls “heterophobia.” In other words, a desire for social distinction, where the tourist, often seen as wealthy, noisy, or thoughtless, becomes the symbol of gentrification and territorial imbalance.

A word loaded with history

The very term “tourist” has carried a pejorative nuance since its invention at the end of the 18th century. It was used to mock those considered frivolous, overly curious, incapable of traveling “seriously.” Today, the denunciation of “overtourism” is its modern heir: a way to disdain popular tourism as mass culture was once despised.

Yet, as the geographer reminds us, tourism creates imbalances, but no more than commerce, agriculture, or transport. Making it the sole scapegoat mainly reflects an identity and social tension.

Finding balance

The challenge for Haute-Savoie is therefore to invent a more sustainable tourism model without tipping into rejection. Some municipalities have understood this: regulation of holiday rentals, limiting car traffic around Lake Annecy, promoting soft mobility or four-season tourism.

Because beyond the numbers and controversies, tourism remains an essential part of the local economy and a tremendous lever to share the beauty of the Alps. Refusing crowds does not mean refusing welcome: everything is a matter of balance.

Between preservation and openness, Haute-Savoie must learn to combine love for its territory and hospitality. Without falling into this new form of intolerance that is tourismophobia.